Speaker

Ehab Akkary, MD, FACS, FAACS

Ehab Akkary, MD, FACS, FAACS

Akkary Surgery Center, Morgantown, WV

Dr. Akkary started his practice in 2008 as an Academic Bariatric Surgeon and gradually shifted to Community based Cosmetic Surgery. He is Board Certified in General Surgery by the ABS and Board Certified in Cosmetic Surgery and Facial Cosmetic Surgery by the American Board of Cosmetic Surgery and the American Board of Facial Cosmetic Surgery. He practices in WV and PA where he performs wide variety of Cosmetic Surgery at AAAHC accredited facilities. Dr. Akkary is devoted to the field of Cosmetic Surgery, he is a Fellow of the AACS. He serves multiple committees at the AACS and the ABCS and he is a reviewer for multiple journals including JAACS.

Abstract

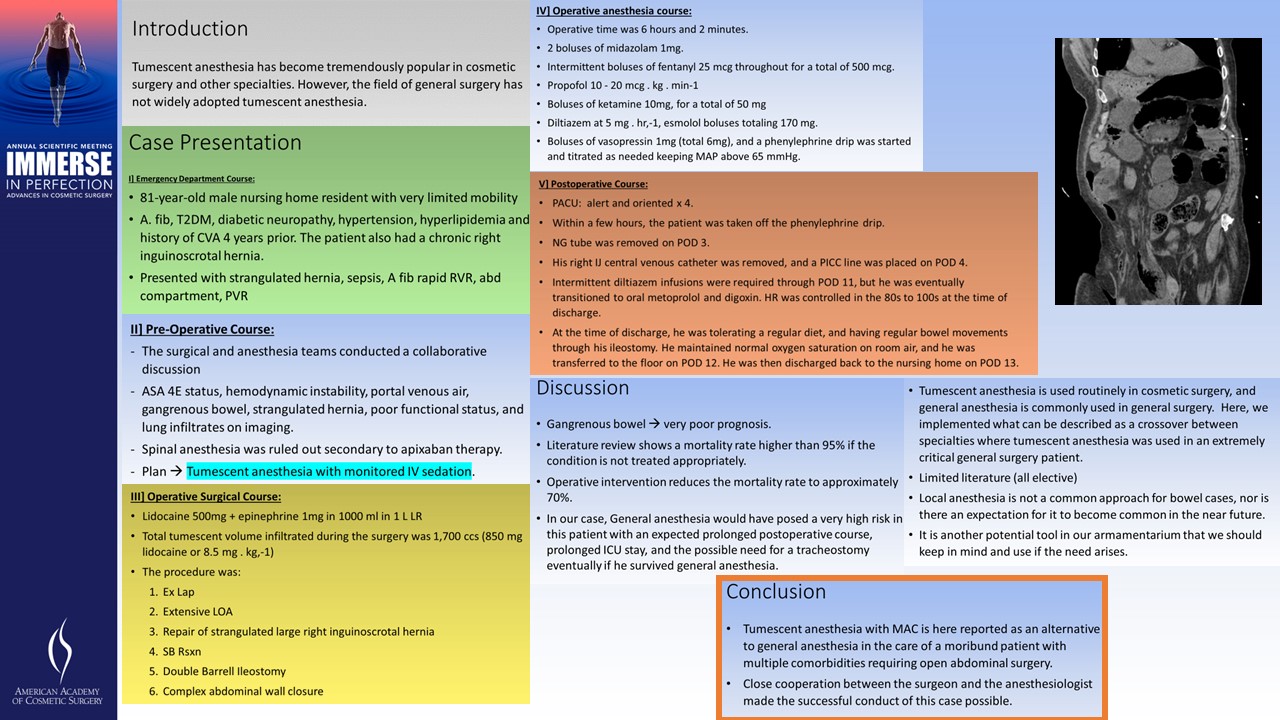

Introduction: Tumescent anesthesia has become tremendously popular in cosmetic surgery and other specialties. However, the field of general surgery has not widely adopted tumescent anesthesia. Many general surgeons and anesthesiologists are not familiar with the technique and how to implement it into their practice. In this article, we present a case of tumescent anesthesia in a critically ill general surgery patient who presented with an acute life-threatening surgical emergency. The patient was assessed to be a very high risk for general anesthesia, and after collaborative discussion between the surgical and anesthesia teams, the decision was made to proceed with surgery under monitored IV sedation with tumescent anesthesia. The patient had an uneventful recovery and survived a very high mortality surgical emergency.

Case Presentation:

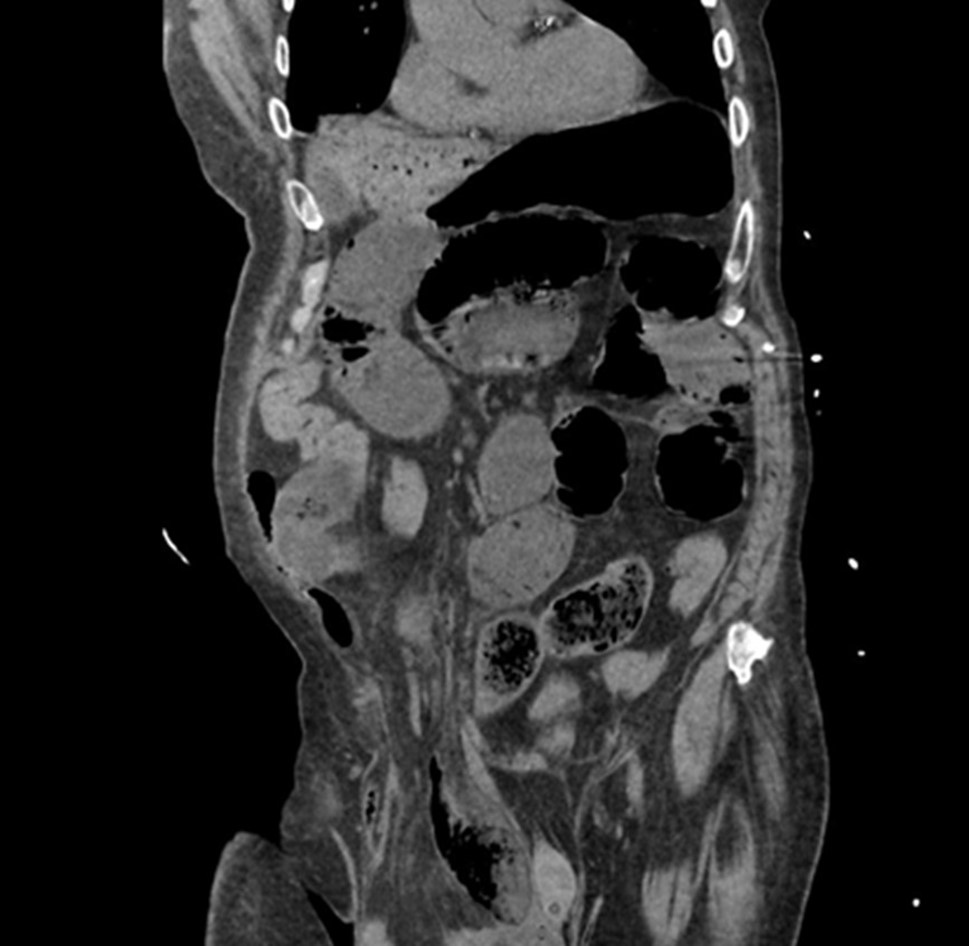

I] Emergency Department Course: An 81-year-old male nursing home resident with very limited mobility who had multiple comorbidities, including atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, diabetic neuropathy, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and history of CVA 4 years prior. The patient also had a chronic right inguinoscrotal hernia. He presented to the emergency room with nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain of 1 day duration. On physical exam, weight was 99.8 kg, BMI 30.8 kg/m2, the patient was borderline hypotensive (blood pressure 94/62), tachycardic (120 beats/min), and tachypneic (34 breaths/min). He had a distended abdomen with incarcerated large right inguinoscrotal hernia. Lab work demonstrated potassium 5.1 mEq/L, creatinine 1.4 mg/dl, and WBC 18,400 cells per cubic millimeter. CT scan showed bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, large right inguinoscrotal hernia with high-grade small bowel obstruction. There was extensive gas in a branching pattern throughout the left hepatic lobe extending to the surface of the liver consistent with portal venous air and suspected bowel necrosis (See attached figure). On presentation, the patient was in atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, he was also anticoagulated on apixaban 5 mg po bid. The patient was placed on diltiazem infusion achieving heart rate control (a decrease in his heart rate to the 70s), and was resuscitated with IV fluids. Patient and family requested “everything to be done”. The patient was subsequently taken to the OR on an emergency basis.

II] Pre-Operative Course: Preoperatively, the surgical and anesthesia teams conducted a collaborative discussion regarding the patient's condition and his high risk of general anesthesia given his extensive comorbidities, ASA 4E status, hemodynamic instability, portal venous air, gangrenous bowel, strangulated hernia, poor functional status, and lung infiltrates on imaging. Spinal anesthesia was a consideration but was ruled out secondary to apixaban therapy. After weighing all the options, tumescent anesthesia with monitored IV sedation was decided upon. On airway examination, the patient had a Mallampati III airway, with normal TM distance, limited neck extension, fair mouth opening, and poor dentition with many missing teeth. No wheezing, no appreciable rales, and no heart murmurs were present. The patient arrived to the preoperative holding area with two peripheral IVs; a 22g in the right forearm, and a 20g in the left antecubital fossa. Initially, diltiazem 5 mg . hr-1 was the only vasoactive infusion. A left NG tube was in place. The patient was retching, and during the anesthesia interview, he began to show altered mental status with progressive worsening, indicating potential rapid decompensation. His HR was 150s-160s with transient increases into the 180s.

While planning to utilize tumescent anesthesia and monitored anesthesia care (MAC), a backup of conversion to general endotracheal anesthesia (GETA) was available. Upon arrival to the OR, his HR was reduced to the 100-120s using boluses of esmolol. A bolus of fentanyl 25mcg was given. A propofol infusion of 10 mcg . kg . min-1 was started. In addition to generous amounts of intravenous fluids, two boluses of phenylephrine 50 mcg were also given. As the patient became sedated, his vital signs stabilized with a MAP in the 70s.

III] Operative Surgical Course: Operative surgical course: Each liter of tumescent solution contained lidocaine 500mg, and epinephrine 1mg in 1000 ml Lactated Ringer’s solution. Total tumescent volume infiltrated for analgesia during the surgery was 1,700 ccs (850 mg lidocaine or 8.5 mg . kg,-1), well beneath a published maximum dose of 28 mg . kg-1 for tumescent anesthesia without liposuction. The abdomen was prepped and draped in the standard surgical fashion after IV sedation commenced. Serial injections of the abdominal wall were made in the midline with tumescent solution using a 20 cc syringe with a 25-gauge needle. A small incision was made in the supra-pubic area and the supra-umbilical area in the midline using a 15 blade scalpel. Then the tumescent infusion cannula was introduced and a tumescent infusion pump was used to infiltrate the abdominal wall. The abdominal cavity was accessed without difficulty. There was transudate noted on entry and this was suctioned. Exploratory laparotomy revealed severe bowel dilation and the bowel had emerged through the incision upon entry of the abdomen indicating compartment syndrome. Examination of the abdomen showed no evidence of succus, stools or pus in the peritoneal cavity. The bowel was gently reduced back into the peritoneal cavity and a gangrenous loop was identified in a strangulated right inguioscrotal hernia. There were extensive adhesions in the right lower quadrant and there was also omentum incarcerated in the hernia. Lysis of adhesions was done using sharp dissection and electrocautery freeing the bowel and omentum. No tumescence was needed for gentle digital bowel manipulation, but tumescence was injected using a 25-guage needle into the prospective planes prior to any cutting, suturing or cauterization throughout the procedure. Continuous communication with the anesthesia team was maintained to determine when more tumescent injections were needed. This was extremely important in providing proper analgesia. The surgery performed was exploratory laparotomy, lysis of adhesions, right inguinal hernia repair, small-bowel resection, ileostomy and complex abdominal wall closure.

IV] Operative anesthesia course: Tumescent local anesthetic was first administered 15 minutes following entry to the OR. The patient, while altered and disoriented, could still give feedback for comfort and pain levels. He was comforted throughout the entire procedure. He appeared subjectively comfortable during the operation. Operative time was 6 hours and 2 minutes. The patient was given two boluses of midazolam 1mg. He received intermittent boluses of fentanyl 25 mcg throughout for a total of 500 mcg. Ninety minutes into the procedure, the anesthesia team attempted to increase the propofol rate to 20 mcg . kg . min-1 to increase the patient’s comfort, but the patient’s BP wouldn’t tolerate even this small increase, despite calcium supplementation and further boluses of phenylephrine. Instead, the anesthesia team started boluses of ketamine 10mg, for a total of 50 mg by the end of the case. The surgeon re-localized as needed throughout the procedure. Despite maintaining the diltiazem at 5 mg . hr,-1 the patient continued to need repeated esmolol boluses totaling 170 mg. At several points during the procedure, the patient required boluses of vasopressin 1mg (total 6mg), and a phenylephrine drip was started and titrated as needed keeping MAP above 65 mmHg.

A total of 2,600 ml of IV crystalloid fluid was given, with 120 ml of urine output, and 1,150 ml of gastric output. Blood loss was 30 ml. Although the anesthesia team was continuously prepared to convert to GETA if needed, general anesthesia was avoided.

V] Postoperative Course: Within an hour of PACU arrival, the patient was doing much better. He was now calm, no longer retching, and was back to baseline mental status; alert and oriented x 4. Within a few hours, the patient was taken off the phenylephrine drip. Lactate improved from 4.7 to 3.1 mmol . L.-1 He was complaining of mild SOB, which was treated with incentive spirometry, and his SOB resolved by POD 2. His NG tube was removed on POD 3. His right IJ central venous catheter was removed, and a PICC line was placed on POD 4. Intermittent diltiazem infusions were required through POD 11, but he was eventually transitioned to oral metoprolol and digoxin. HR was controlled in the 80s to 100s at the time of discharge. At the time of discharge, he was tolerating a regular diet, and having regular bowel movements through his ileostomy. He maintained normal oxygen saturation on room air, and he was transferred to the floor on POD 12. He was then discharged back to the nursing home on POD 13.

Discussion: The diagnosis of gangrenous bowel carries a very poor prognosis. Literature review shows a mortality rate higher than 95% if the condition is not treated appropriately. Operative intervention reduces the mortality rate to approximately 70%. In our case, the patient had the grave diagnosis of gangrenous bowel in addition to extensive comorbidities and compromised cardiac and pulmonary statuses. Strategic and thorough planning took place between the surgery and anesthesia teams to be able to get the patient through this surgery while minimizing risk. Spinal anesthesia was not an option as the patient was actively on anticoagulation. General anesthesia would have posed a very high risk in this patient with an expected prolonged postoperative course, prolonged ICU stay, and the possible need for a tracheostomy eventually if he survived general anesthesia. The finalized plan was to proceed with local anesthesia using tumescent solution under monitored IV sedation with general anesthesia as the backup plan. The complex procedure was completed successfully without the need for intubation or general anesthesia. The postoperative course of the patient was excellent and relatively without incident. The patient was awake, alert and oriented in PACU and was very thankful to the surgery and anesthesia teams that he survived the surgery. He continued to recover in ICU and was subsequently transferred back to the nursing home in stable condition after approximately a 2-week hospital stay. While this is not expected to be a routine everyday approach for exploratory laparotomy with bowel resection and complex closure, it is a technique that is worth knowing and mastering for when the need arises. Based on the assessment and evaluation of this patient, this was our best approach to get him through the surgery and postoperative recovery safely. To our knowledge, this is the first case report, to date, describing the use of tumescent anesthesia in an emergency bowel resection. Tumescent anesthesia is used routinely in cosmetic surgery, and general anesthesia is commonly used in general surgery. Here, we implemented what can be described as a crossover between specialties where tumescent anesthesia was used in an extremely critical general surgery patient. There are very few articles in the literature describing the use of local anesthesia in bowel surgery electively. Sebastian et al published their experience with 8 patients who underwent oncologic colon resections. They concluded that doing these procedures under local anesthesia with sedation was feasible in properly selected cases. Another study by Tavassoli et al looked at performing sigmoid resection under local anesthesia in patients who are high risk for general or regional anesthesia. The study included 14 patients and concluded that local anesthesia was a reasonable option in these high risk properly selected patients. Overall, there is a paucity of research in the literature when it comes to using local anesthesia for bowel surgery. The daily reality of life in the operating room shows that sometimes there are extreme cases where such a course of action becomes necessary to maximize patient safety. Local anesthesia is not a common approach for bowel cases, nor is there an expectation for it to become common in the near future. Ultimately, though, it is another potential tool in our armamentarium that we should keep in mind and use if the need arises.

Conclusion: Tumescent anesthesia with MAC is here reported as an alternative to general anesthesia in the care of a moribund patient with multiple comorbidities requiring open abdominal surgery. Close cooperation between the surgeon and the anesthesiologist made the successful conduct of this case possible.

Take Home Message

Tumescence anesthesia is widely used in cosmetic surgery as well as dermatology, vascular surgery, reconstructive plastic surgery, breast surgery and other specialties. The use of tumescence anesthesia is general surgery has been limited. Tumescence anesthesia with sedation might represent an appropriate method to undergo surgical intervention in critically ill patients if the need to avoid general anesthesia arises.